Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

Home, as we all know, is where the heart is. But in “Terrain” by Genevieve Valentine, published right here on Tor.com last March, both home and heart have been hard to come by.

At the outset of Valentine’s affecting novella we find our main character Faye racing to make herself scare. The men from the railroad company have come to ask Elijah about buying his land, and as people of colour, she and the other four farmhands know to stay out of their way.

Welcome, one and all, to the Old West, where racism is rife, and violence wields a long knife in the night.

But Elijah was white, and kindhearted, and had made friends when he lived in River Pass—Harper at the general store still set things aside for him. Elijah had no reason to fear two men who smiled and seemed polite; once or twice, he laughed.

Bad sign, Faye thought.

She’s right. The men won’t take no for an answer. Elijah’s fifty acres lie directly in the path of the proposed railroad: a railroad almost certain to bring wealth to the residents of River Pass, its “tracks like threads to draw white men closer together.” Without Elijah’s land, the train will have no choice but to go to the next town over, and that’s not a notion the locals like.

Elijah, however, has his reasons for resisting. He and his hands—though he at least treats them like equals—don’t just grow crops on the farm; the land is also the base of operations for Western Fleet Courier, a Pony Express competitor with a progressive delivery method: its riders make use of monstrous dogs rather than mere mortal horses.

A dog has six legs. Each one is thin, and tall as a man, and arched as a bow, and in their centre they cradle the large, gleaming cylinder of the dog’s body. The back half conceals a steam engine, with a dipping spoon of a rider’s seat carved out ahead of it, with levers for steering and power, and just enough casing left in front to stop a man from hurtling off his seat every time the dog stops short.

It looks ungainly. The casing jangles, and the legs seem hardly sturdy enough to hold it, and when someone takes a seat it looks like the contraption’s eating him alive.

But legs that seem ungainly in the yard are smooth on open territory, and dogs don’t get skittish about heights or loose ground, and when scaling a rock face, six legs are sometimes better than four.

These mechanical animals could make all the difference when the townsfolk get wind of Elijah’s refusal to be uprooted, and the lynching begins.

I have a hard time putting my finger on why it’s taken me nearly a year to read this very fine fiction, but I’ll try. To the best of my recollection, last March was an abnormally awesome month for genre fiction fans. I had more books to read and review than I knew what to do with, so though I put “Terrain” in my Pocket the moment I spotted it, 2013 wore on inexorably; a year, clearly, with no shortage of shinies.

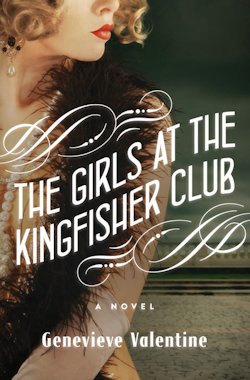

Now, with news of Valentine’s next novel proper doing the rounds—read all about it: The Girls at the Kingfisher Club (née Glad Rags) is due in June—what better time than this to revisit it?

An emotional story about finding a place to call your own—a home away from home—and fighting to defend said when outsiders intrude upon these private places, ‘Terrain’ has quite a lot in common with Valentine’s great debut. Like Mechanique: A Tale of the Circus Tresaulti, it concerns the cost of so-called progress—and both are of course steampunk stories.

Me, I don’t like steampunk in the least. The aesthetic is certainly interesting, and there’s storytelling potential, yes, but so much of the steampunk I’ve read—from writers like Lavie Tidhar and Cherie Priest, whose other work I often enjoy—has had, in my eyes, little else to recommend it. Mechanique was a rare and precious exception which quite literally incorporated the form into its characters and narrative.

Here, however, the dogs are essentially set dressing. Though one does play a part in the catastrophic finale, they’re not at all necessary.

Happily, there’s enough to “Terrain” that this missed opportunity doesn’t prove too injurious. What makes today’s belated tale tremendous is its telling—Valentine walks the line between terse and tender with well-judged warmth and wisdom—in addition to the inevitably heartrending relationship between Faye and Frank.

It was easy to mistake Frank and Faye. The twins looked like their mother, the high brow and strong jaw, and they had the matching, flinty expressions of a lot of the Shoshone children who were sent to the white school. It made Frank look like a warrior, and Faye look troubled.

More closely tied to one another than lovers, the twins are torn apart by the attacks on the farm. “If he would only leave, she’d go tonight, head for the mountains, never stop moving,” but Frank means to make a stand, to fight for what’s right. Sometimes, sadly, doing the right thing is wrong.

“Terrain” is a hard-hitting depiction of the real horrors of human history that doesn’t pull its punches, a bittersweet story about home, and a mournful ode to “land, and loneliness.” This last is according to the author, who casts her narrative net wide in this unforgettable fiction, and captures most everything she intended.

The Girls at the Kingfisher Club can’t come soon enough.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.